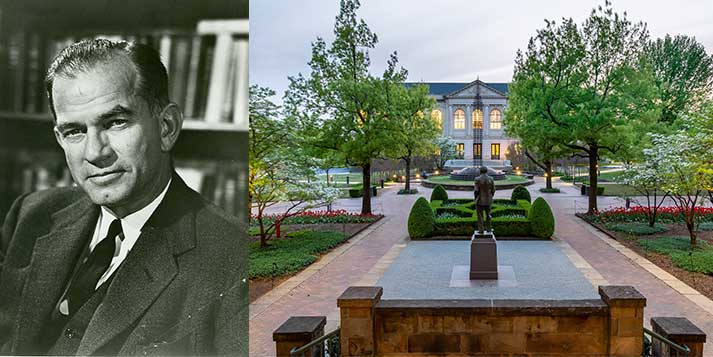

J. William Fulbright

The Fulbright Paradox

The University of Arkansas recognizes that Sen. Fulbright’s record on civil rights issues does not align with the university’s core values and that many have little awareness of this history. Meanwhile, some are unaware of his extensive actions to promote peace and international security, including through educational exchange, and other laudable aspects of his record of service.

All of these conditions provide an opportunity for us to embrace our mission of teaching and learning, to engage a more complete history about one leader’s contradictory legacy in the context of his times, and to use the experience in the present to continue our work to build a better campus and world.

The hope of the university is that our community explores the full history of Sen. Fulbright, to better understand both why he is honored, and also why the use of his name and statue on our campus can seem troubling, so that together we can build a future in which every member of our community feels a sense of belonging.

We acknowledge our history so that we can learn and grow as individuals and as a community.

The following overview, timeline and resources are provided to help the campus community take an initial step in that direction.

The overview, divided into separate sections, will also be displayed on campus near the Fulbright statue. Installation is currently expected in 2022. In the meantime, temporary signage with a link to this online resource has been placed just north of the statue.

Arkansas Connections

Student Government President

From Fayetteville, J. William Fulbright graduated from the University of Arkansas, where he served as student government president and played football for the Razorbacks from 1921-24.

University President

The Rhodes scholar returned to campus as a faculty member, after earning a law degree at George Washington University. In 1939, Fulbright became the nation’s youngest college president at the age of 34, when he was named to lead the University of Arkansas.

U.S. Senator

He represented Arkansas as a U.S. senator for 30 years from 1945-1974, after finding success in his first political race and serving one term as a U.S. representative from 1942-1944. He worked with six presidents during his time as an elected official.

Presidential Medal of Freedom

President Bill Clinton, fellow Arkansan and former University of Arkansas faculty member, presented Fulbright with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1993.

University Recognition

In 1982, the university named the College of Arts and Sciences after Fulbright.

In 1983, the university established the Fulbright Institute of International Relations with the goal of making the university a center for the study of international relations, with emphasis on Sen. Fulbright's internationalism, public diplomacy, media and foreign policy.

In 1998, the Fulbright Peace Fountain was dedicated in honor of his belief that “education, particularly study abroad, has the power to promote tolerance and understanding between nations.

Four years later, a statue of Fulbright was dedicated, and former President Clinton spoke during the dedication ceremony.

Fulbright’s (1905-1995) ashes were interred near campus at Evergreen cemetery.

Fulbright Program and Internationalism

The Fulbright Program

Sen. Fulbright may be best known for a scholarship program he established early in his political career. Within weeks of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, and the end of World War II, he announced his intention to introduce legislation to create an international educational exchange program.

The Fulbright Program's aim: “to bring a little more knowledge, a little more reason, and a little more compassion into world affairs and thereby increase the chance that nations will learn at last to live in peace and friendship.” — Senator J. William Fulbright, Foreward, The Fulbright Program: A History

Established by an act of Congress during the next year, the Fulbright Program was designed to promote peace and understanding through educational exchange. It is now the world’s largest international scholarship program.

Since 1946, more than 400,000 ‘Fulbrighters’ from more than 160 countries have benefited from what has become one of the most widely known and prestigious of all scholarships. Awardees include dozens of heads of state or government, and multiple Nobel Prize and Pulitzer Prize winners.

In a speech before the Council on International Educational Exchange in 1983, Fulbright said educational exchange “can turn nations into people, contributing as no other form of communication can to the humanizing of international relations.”

United Nations, Marshall Plan, NATO

During his time as a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, he authored the Fulbright Resolution, which supported international peacekeeping initiatives and encouraged the United States to participate in what became the United Nations. Later, he supported the Marshall Plan, providing aid to rebuild Western Europe following World War II, and the creation of NATO – the North Atlantic Treaty Organization – an international alliance that includes 30 nations in Europe and North America.

McCarthyism

As a U.S. senator, Fulbright challenged the anti-Communist accusations of Joseph McCarthy and his attacks on the Fulbright Program, helping convince a majority of senators to join Fulbright in censuring McCarthy.

In one of the hearings related to ambassador and judge Philip Jessup, Fulbright seemed to sum up what he thought about McCarthyism, telling McCarthy, “You can put together a number of zeros and still not arrive at the figure one.”

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Fulbright holds the record as the longest-serving chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee with a 16-year stint from 1959-1974.

Vietnam War

While he initially supported the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1964 that led to an escalation of the Vietnam War, he became critical of the effort, leading a series of nationally televised hearings about the conflict and how it came about. In 1966, his book, The Arrogance of Power, challenged the justification for the war and reinforced his belief that Cold War politics necessitated and sustained it.

Segregation and Civil Rights

Early Opposition to Desegregation

As early as 1950, Fulbright offered an amendment to give soldiers the choice of whether to serve in a racially integrated unit. Two years later he opposed statehood for Alaska because he believed its congressional delegation would vote in favor of civil rights legislation.

Brown v. Board of Education and the Southern Manifesto

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case confirmed that state laws establishing segregated schools are unconstitutional.

In 1956, Senator Fulbright joined more than 19 Southern senators and 77 representatives in signing a counter statement to the ruling – the Declaration of Constitutional Rights, informally known as the Southern Manifesto – that essentially opposed racial integration in public places.

The entire congressional delegations from Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia, and many other congressional members from Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee and Texas signed on in support of the manifesto.

Little Rock Central High School Integration Crisis

In 1957, when Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus prevented Black students from entering the segregated Little Rock Central High School, Fulbright did not challenge Faubus. After President Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened, the first group of nine Black students, known as the Little Rock Nine, were allowed to attend classes.

Civil Rights Acts

Along with most Southern legislators, Fulbright voted against the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964. He participated in a filibuster of the act that outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin, prohibiting employment discrimination, unequal voting registration requirements, and segregation in schools and public accommodations. However, in 1972, Sen. Fulbright voted in favor of strengthening the enforcement powers of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Fair Housing Act

Fulbright voted against the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which would prohibit discrimination concerning the sale, rental and financing of housing.

Voting Rights Act

Fulbright opposed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, but in 1970 voted for a five-year extension of the Voting Rights Act, supporting the continuation of special provisions outlawing discriminatory voting practices, especially in the South.

Judicial Nominations

In 1967, Fulbright voted in favor of the nomination of Thurgood Marshall, the first Black U.S. Supreme Court justice. In 1970, he voted against the Supreme Court nomination of G. Harrold Carswell, who had once advocated for white supremacy.

Other Resources

Books and Biographies

- Arndt, Richard T. and Rubin, David L. (1993) The Fulbright Difference: 1948-1992 (Studies on Cultural Diplomacy and Fulbright Experience. Transaction Publishers.

- Austin, Betty. (1995) J. William Fulbright: A Bibliography. ABC-Clio, LLC.

- Berman, William C. (1988) William Fulbright and the Vietnam War: The Dissent of a Political Realist. Kent State University Press.

- Brogi, Alessandro, Giles Scott-Smith, and David J. Snyder. (2019) The Legacy of J. William Fulbright: Policy, Power, and Ideology. University of Kentucky Press.

- Brown, Eugene. (1985) J. William Fulbright: Advice and Dissent. University of Iowa Press.

- Burns, Thomas M. (2014) The Zen of Fulbright: The Unofficial Guide to Fulbright Scholarships. Don Davis Publishing.

- Dynes, Russell R. (1987) Fulbright Experience, 1946-1986: Encounters and Transformations. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Fulbright, J. William. (1989) The Price of Empire. Pantheon.

- Fulbright, J. William. (1972) The Crippled Giant: American Foreign Policy and It’s Domestic Consequences. Random House.

- Fulbright, J. William. (1966) The Arrogance of Power. Random House.

- Fulbright, J. William. (1964) Old Myths and New Realities. Random House.

- Meyer, Karl E. (1963) Fulbright of Arkansas: The Public Positions of a Private Thinker. Robert B. Luce, Inc.

- Powell, Lee Riley. (1996) J. William Fulbright and His Time: A Political Biography. Guild Bindery Press.

- Stuck, Dorothy and Snow, Nan. (1997) Roberta: A Most Remarkable Fulbright. University of Arkansas Press.

- Woods, Randall Bennett. (1998) J. William Fulbright, Vietnam, and the Search for a Cold War Foreign Policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Woods, Randall Bennett. (1995) Fulbright: A Biography. Cambridge University Press.

Special Collection of J. William Fulbright Papers

The University of Arkansas Libraries’ Special Collection of J. William Fulbright Papers online is an excellent resource and includes finding aids, digital collections, related collections and links to related international education organizations.

Digital Collections

The University of Arkansas Libraries’ digital collection, Fulbright Speaks, includes documents related to the “Southern Manifesto” and other issues as well as speeches and other items related to the Fulbright Program.

Related Collections

In addition to the Fulbright papers, the University of Arkansas Libraries house one of the country's largest collections on international education and cultural exchange.

Special Collections is the active collecting repository for:

- Council for International Exchange of Scholars (CIES) Records (MC 703)

- NAFSA: Association of International Educators (MC 715)

- Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Historical Collection, CU (MC 468)

Please see the International Education and Cultural Exchange guide for a list of related collections housed in Special Collections.

Related International Education Organizations

- Fulbright Scholar Program (a program of the United States Department of State Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs)

- Institute of International Education (IIE)

- J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board (FFSB)

- NAFSA: Association of International Educators

- GlobalTiesUS (NCIV)

- Meridian International Center

- Fulbright Alumni Association

How We Got Here

Campus Concerns

Several student and other constituent groups raised concerns in 2020 about the treatment of minorities on campus, specifically Black students, and demanded removal of the Fulbright statue and his name from the College of Arts and Sciences as well as removal of the name of Charles Hillman Brough, former Arkansas governor, from a dining hall.

University Committee Explores Connections, Makes Recommendations

A diverse committee of Fulbright College students, faculty, staff, and alumni was formed to explore the university’s connections to Fulbright and Brough, make recommendations on the three matters and render a report in early 2021.

In April 2021, the committee recommended the removal of the names from the college and dining hall and the removal of the Fulbright statue.

Earlier that month, Act 1003 of 2021 took effect, stating that “A historical monument shall not be relocated, vandalized, damaged, destroyed, removed, altered, renamed, rededicated or otherwise disturbed.”

Chancellor Steinmetz Makes Recommendations

In May 2021, after listening to a wide array of stakeholders and seeking feedback regarding the committee’s recommendations, then-Chancellor Joseph E. Steinmetz ultimately advanced a differing recommendation to U of A System President Donald R. Bobbitt – to move the statue to a more appropriate location so context could be added, to remove the Brough name from the dining hall, and to leave the Fulbright name on the college itself.

U of A System President Makes Recommendations

President Bobbitt responded to the campus recommendations in a letter to the University of Arkansas System Board of Trustees in July 2021, recommending that the college name should remain, the statue should remain at its present location, and that new information be added to present a more complete history of Fulbright the man, and that the Brough name could be removed from the dining hall. He cited external factors that prevent moving the statue, including the recently passed Act 1003 of 2021.

U of A System Board of Trustees Resolution

The Board of Trustees approved President Bobbitt’s recommendations in a July 2021 resolution.

Digital History Launched

This overview of Sen. Fulbright’s life and career, links to additional resources and a summary of recent events, was launched late in 2021 in an effort to provide an overview of the full history about one leader’s contradictory legacy, and to use the experience to continue the university’s work to build a better campus and world.

Overview Planned Near Statue

The installation of signage providing an overview of Sen. Fulbright’s life and political career is planned for 2022. The current plan is to add separate panels on campus near the statue. In the meantime, temporary signage with a link to this online resource has been placed just north of the statue.